MORMON SETTLERS OF ARIZONA

I applied insights developed with French Algerian studies to a consideration of settlers of Arizona. In 2003-4, I conducted research among descendants of early Mormon families in Arizona and studied public history-making, advancing a study of “settler colonial historical consciousness.

MORMON FORESTDALE

This article first appeared in Journal of the Southwest, Summer, 2005, Vol. 47, No. 2.

ABSTRACT

Settled by Mormons beginning in 1878, Forestdale, Arizona, was abandoned in 1883 when it was determined to be within the boundaries of the White Mountain Indian Reservation. Narratives among the settlers' descendents highlight a uniform understanding of the event that diverges from archival sources but sheds light on the importance of the event for the community. Some uniformity may be the result of US senator Henry Fountain Ashurst's unsuccessful 1915-21 attempts to win compensation for Forestdale residents by arguing that the reservation boundaries had been moved and that settlers had been deceived by inaccurate maps and official information. In reality, however, the settlers may have known they were trespassing on Indian lands. The dispossession narratives should be considered within their larger sociopolitical context, with an understanding of the values and meanings these persistent memories hold.

SETTLER HISTORICAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE LOCAL HISTORY MUSEUM

This article originally appeared in Museum Anthropology, Vol. 34, Iss. 2, pp. 156–172. Read it here or download PDF.

Exiting Interstate 40 for Holbrook, Arizona, one passes a contemporary monument of a cowboy riding high atop a precarious tower of petrified logs, with a diminutive person, presumably a Native American, looking up at him. Further along, one passes a series of flashy Route 66–era motels, tired-looking stores adorned with murals of Indians in feathered headdresses, and large green dinosaur statues advertising petrified wood and Indian artifacts. Turning onto a side street, one encounters a large grassy park with a bandstand, war memorial, and an impressive sandstone building identified as the Navajo County Museum. This is one of several local historical museums that have proliferated in this area of Arizona in the past several decades, and which present excellent examples of the local character of public history making in the United States. (Also considered in this article are the Apache County Historical Society Museum in St. Johns, Arizona; the Graham County Historical Museum in Thatcher, Arizona; and the Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society in Pima, Arizona; see Figure 1.) Like other local museums, they rely on local residents for financial backing and material collections (Levin 2007). They also exemplify a widespread yet largely unaware settler colonial historical consciousness. In this article, I first outline characteristics of settler societies likely to emerge in particular ways of framing the national or local past and then turn to their manifestation in eastern Arizona.1

Figure 1. Map of Arizona’s counties and tribal lands. (William G. Dohe AIA.)

First, what is meant by “settler colonialism”? Scholarship in Native American studies, genocide studies, the Native Hawaiian sovereignty movement, and Australian historiography suggests that we view the contemporary United States as an ongoing settler society yet to undergo decolonization (Biolsi 2005; Coombes 2006; Fujikane and Okamura 2010; Jacobs 2009; Kauanui 2008; Moses 2004; Philips 2005). Patrick Wolfe’s insights stemming from his study of Australia are particularly illuminating in this regard. Wolfe highlights a “logic of elimination” as settler colonialism’s distinguishing feature: “settler colonialism is first and foremost a territorial project, whose priority is replacing natives on their land rather than extracting an economic surplus from mixing their labor with it” (2008:103). He outlines positive and negative dimensions of this form of colonialism: negatively, “it strives for the dissolution of native societies,” and positively, “it erects a new colonial society on the expropriated land base” (Wolfe 2008:103). He suggests that we not view elimination as an event or a series of events, but rather as an organizing principle of settler-colonial society. Following frontier violence, “settler societies characteristically devise a number of often coexistent strategies to eliminate the threat posed by the survival in their midst of irregularly dispossessed social groups” (Wolfe 2008:103). These strategies include not only extermination and expulsion but also assimilationist projects such as breaking down native title into alienable landholdings, native citizenship, child abduction, and religious conversion—all ultimately “eliminatory strategies” that “reflect the centrality of land” (Wolfe 2008:103).

If elimination is indeed an organizing principle of settler society, it should yield distinctive ways of conceptualizing the past, a settler-colonial historical consciousness. “Historical consciousness” here refers to the ways that everyday people as well as professional historians understand the past (Seixas 2004:10), which in other disciplines is sometimes termed “collective memory” (Conway 2010). Scholars of settler colonialism are turning to this topic, asking how “the long history of contact between indigenous peoples and the heterogeneous white colonial communities ... has been obscured, narrated and embodied in public culture in the twentieth century” (Coombes 2006:1). This “memory work” is quite advanced in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa. Through a close analysis of one museum’s collection in particular, I hope to contribute to a parallel paradigm shift currently under way in the United States by illustrating what a “settler- colonial” account of the local past might entail.1

THE LOCAL HISTORY MUSEUM

Michael Ames called for scholars to return to the museum, if not to learn from the objects found within, then to move beyond the object to include the “museum itself as an artefact of our society” (1992:44) Museum activities can be explored as cultural performances that transmit a variety of intended and unintended messages: they communicate essential values and serve as political instruments of the state, monuments to the benevolence of the elite, and sources of local pride. In doing so, they become important sites in the dissemination of hegemonic ideologies and the construction of knowledge more generally (Ames 1992:101).

The museum’s reproduction of hegemonic ideas may be best exemplified by history museums, which in the United States have proliferated exponentially since World War II. In 1978, cultural historian Thomas Schlereth (2004:335) argued that historical museums exert “inordinate influence” on Americans’ views of the national past. At that time, he identified several common problems with U.S. history museums, including their tendency to homogenize and sanitize the past. He ended his essay on a populist note, encouraging teachers and museum curators to show the “average citizens various ways of knowing themselves and their communities through an understanding of their own past and the pasts of others” (Schlereth 2004:344).

Despite the proliferation of history-related popular media, the museum still plays a key role in how Americans relate to their past. According to their extensive survey-based research conducted in the 1990s, Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen (1998) found that Americans encounter the past through multiple arenas, including family gatherings, school, conversations, television, and movies. The museum, however, was viewed as the most trustworthy of these sources, far more than television programming and even high school history teachers (Rosenzweig and Thelen 1998:32). While anthropological studies of American history museums have proliferated in recent years, they have emphasized the more prominent national examples (Gable and Handler 2006; Handler and Gable 1997; Kahn 1995; Wallace 1996); the smaller local history museum remains understudied.

In the United States, local history museums are ubiquitous yet diverse institutions that defy easy generalization. They range from living history museums in which participants play themselves as historical figures (such as Arthudale, West Virginia) to nostalgic (and largely fictional) recreations of mythical places (such as the Old Cowtown Museum in Wichita, Kansas) to well-funded, multimedia state historical museums (such as the Old State Capitol Museum in Baton Rouge, Louisiana) (Levin 2007). This diversity stems in large part from the very democratic and decentralized nature of public history making in the United States called for by progressive cultural historians such as Schlereth. This decentralization is extreme: indeed, we cannot know with any certainty how many local history museums exist in this country at any given time. According to the American Association of Museums, there have been only two recent attempts to enumerate American museums (1998 and 2000), with the most recent effort by the Institute of Museum and Library Services yielding approximately seventeen thousand five hundred museums.2 The association’s membership can be searched online—1,210 are identified as “history museums,” although this is clearly only a subset of existing museums (and none of the museums studied for this article are included in that list).3 The American Association for State and Local History has identified the “small” museum as a subtype; however, a 2007 survey conducted by the association was inconclusive regarding how such a museum might be defined.4

Aside from regulations guiding nonprofit organization status, there are no universal standards that historical museums must follow; however, their local character can yield predictable results, as James Loewen (1999) found in his study of historic sites and monuments. Because they often stem from local initiatives led by private individuals and volunteer societies, local history museums, like the monuments Loewen reviewed, tell a narrative that best suits their founders, tending to “omit any blemishes that might taint the heroes they commemorate” (Loewen 1999:17). As Loewen quips, such sites proclaim to the visitor that “everything that happened here was good” (1999:17). As we turn to an example from central Arizona, we find that the primary vantage point is a settler-colonial one as well.

NAVAJO COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM

The Navajo County Historical Museum was established in 1981 in Holbrook, Arizona, the county seat since 1895. Ostensibly a project of the county historical society, the museum owes its existence to the efforts of Garnette Franklin, a Holbrook resident from 1919 until her death in 2006 (Rhoden 1999). In the 1970s, Franklin and other members of the Navajo County Historical Society began to lobby the Holbrook City Council for the creation of a regional visitor’s center at the Navajo County Courthouse, a building to be abandoned with the completion of a new county headquarter complex.5 She argued before the City Council that such a center would “bring more revenue into Holbrook,” adding, “it is a real challenge to see how far reaching the effects would be if, with proper planning and use, this historic old building could return Holbrook to the hub city of Northeastern Arizona.”6 Franklin was known locally for her interest in Holbrook’s past. People today speak fondly of her visits to their elementary school classes, and a local resident remembers that whenever an abandoned building was lost to neglect, Franklin was distraught. The resident reminisced, “I can just hear her saying, ‘We’re losing all of our old buildings! We have to do something.’”7

When Franklin and eight other local residents were appointed to the Navajo County Museum Board by the Navajo County Board of Supervisors in 1980, they faced the daunting task of developing and organizing collections.8 They obtained most items through local donations, or “anything they could beg, borrow, or steal.”9 The museum was opened in 1981. Articles in the local newspaper praising people and institutions for their donations illustrate the idiosyncratic nature of the objects received:

The following people have been largely responsible for making the museum a success: Marlin Gillespie, Navajo County Sheriff’s pictures and leg irons; Lewis Turley, pictures from the “Bucket of Blood Saloon ... Millie Maddox, figurines and Apache necklace ... Hilda Frost and the Show Low branch for providing a pioneer display; Mollie Salazar, Spanish combs and mantillas; Frances DeMare, prayer book and pancho ... Cephas Perkins, saddle ... Lamerle Gerwitz, Hogan, arrow heads and Apache basket; Everett Cooley, rifle and artifacts from Fort Apache.10

The museum now comprises the bottom floor of the former courthouse (Figure 2) and is open every day of the week. The museum’s lobby serves as the local Chamber of Commerce headquarters, which provides a staff member to assist tourists. In 1989, approximately 80 percent of the people who visited the chamber also went into the museum, or some 34 thousand people (Fox 1990:11). However, due to perpetual funding shortages, it has a somewhat shabby appearance. Some of the displays appear to be repositories for objects left over from the building’s formeruse as a courthouse. And yet the museum tells a clear story that we might organize into the following four themes: “The Town,” “Prehistory,” “History,” and “Law and Order.11 Each is discussed in turn.

Figure 2. Navajo County Historical Museum. (Photograph: Author.)

The Town

Most museum visitors arrive by car via the interstate (I-40), located a few miles to the north of Holbrook, and thus do not necessarily see the town on their way. The first exhibit orients these visitors with paintings of the old courthouse, the train depot, and railroad crossing; all are original works by Garnette Franklin. We see a photographic image of Henry Holbrook, engineer for the Atlantic Pacific Railroad and the town’s eponymous ancestor. A plaque to the right of Holbrook’s portrait informs us that “John Young, who was a grading contractor for the railroad, named the town after Mr. Holbrook on September 24, 1881, the day the last spike was driven.” To the left of Holbrook’s image is a tall chest that is labeled “Spanish Influence Showcase,” acknowledging a local Hispanic presence. In this large armoire are Mexican blankets, articles of clothing, lace, hair combs, and fans.

The viewer is also instructed to note the replica of the Blevins House and “read the story of the shootout that took place there.”12 A flyer, “Shootout at Holbrook,” features a reproduction of Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens and describes his actions on September 4, 1887. When Owens went to arrest suspected horse thief Andy (Cooper) Blevins at his mother’s house in Holbrook, Blevins tried to shut the door on Owens, and Owens fired his rifle through the door, striking Blevins in the abdomen. As the residents tried to defend their family members, Owens fired again, ultimately killing three men and wounding another. He then left town on horseback “without speaking another word to anyone.” In a separate brochure, we learn that Holbrook was “wilder than Tombstone in the past!”13 The town’s image is thus established. It is a railroad town named after a railroad engineer that soon became a rough-and-tumble frontier town with heroic lawmen braving violent criminals by taking the law into their own hands.

Prehistory

The local past is the focus of the rest of the collection. It is depicted visually through collections of material objects whose organization tells a story and reiterated in textual form in the visitors’ brochure. The first objects displayed are quite ancient ones: pieces of petrified wood and casts of fossils dating to 225 m.y.a. Immediately adjacent to these artifacts are paintings of Native Americans: Navajos in hogans, and a reproduction of a 19th-century studio portrait of the Navajo leader Manuelito.14 These paintings are hung above display cases exhibiting Native American arrowheads and pottery found in unknown locations by various local residents. The overall impression is a representation of the natural backdrop that helps set the stage for the arrival of “the people,” who are the focus of the rest of the museum (Figure 3).

Figure 3. “Prehistory.” Detail of exhibits, Navajo County Museum. (Photograph: Author.)

History

The next set of rooms displays the dwellings, stores, and material culture of local “pioneers,” ancestors of the museum’s founders. We see a recreated drug store, kitchen, barbershop, saloon, and a pioneer bedroom. The brochure instructs us, “Moving across the hall you will find a pioneer kitchen showing the washing machine that was such an improvement over the scrub board.” We are told that the parlor to the right “is typical of a home in the early 1900s. No matter how meager the furnishings each home usually had an organ or piano which provided their entertainment.”15 Carrying this theme further, we are shown upstairs an “old-time” bedroom with “very old and interesting articles used by the early settlers of the area.”16 There is no explicit indication anywhere that the recreated settings are typical of any particular ethnic group or social class.

Law and Order

Although they are the architectural highlight of the historic building, the former courtrooms posed a real puzzle to the historical society. The judge’s chambers and courtroom could not be dismantled without incurring great costs, and yet it was difficult to incorporate these rooms into a historical narrative of interest to tourists. The brochure instructs us to “think of the many trials that were held in this room from 1899 through 1976.” On the front page of the brochure, we learn that while “many notorious trials were held in the stately courtroom ... only one hanging took place in the courtyard.” Sheriff Wattron’s macabre invitation to the hanging of “George Smiley, Murderer,” dated November 28, 1899, is found on display and highlighted in additional brochures available to the visitor. Clearly, museum developers assumed that connecting Holbrook into a wider, well-known “Wild West” template would attract visitors. This theme continues downstairs. Rather than converting the sheriff’s office and jail to some other use, the curators decided that there was value in preserving them as they had been when last used in 1976.

Holbrook’s Past

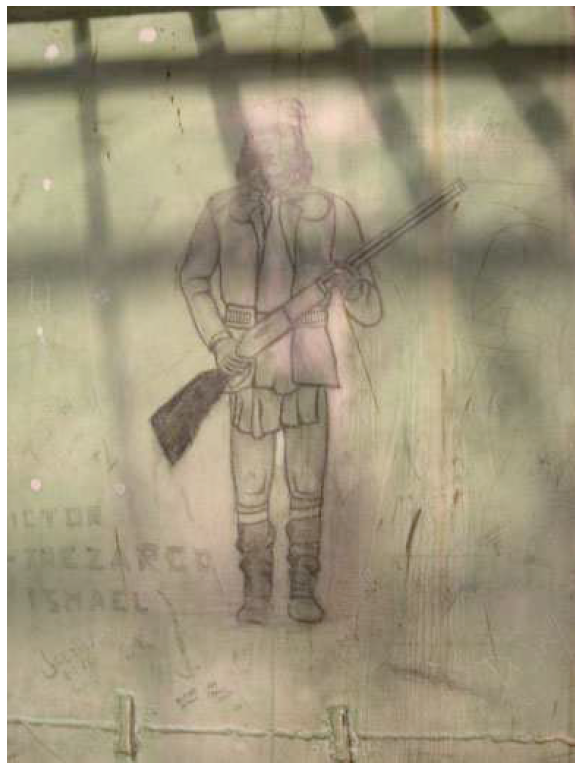

The end result is an exhibit of local history celebrating the area’s Anglo heritage. Other ethnic groups are not completely silenced, however, for artwork drawn by people of presumably Hispanic and Indian origins is also on display—in the jail (Figures 4–8). The power- ful drawings scratched into the walls include images of Geronimo, an Apache crown dancer, Manuelito, the Virgin of Guadalupe, what one presumes is a depiction of pueblo dwellings, and self portraits. If the average visitor did not know that Native Ameri- cans still lived in the area, they would now. The juxta- position of framed photographs of former sheriffs in a display case outside of the jail and pencil drawings on the crumbling ancient jailhouse does more to communicate a racial and ethnic hierarchy than the wording of any text ever could: Native Americans and Hispanic residents, one could easily infer, are a criminal element who belong behind bars, while the descendants of the early “pioneers,” the Anglo “people,” are in charge of their incarceration.

Figure 4. Drawing of Manuelito on prison wall, Navajo County Museum. (Anonymous artist; Photograph: Author.)

Figure 5. Drawing of Apache Crown Dancer on prison wall, Navajo County Museum. (Anonymous artist; Photograph: Author.)

Figure 7. Drawing on prison wall, Navajo County Museum. (Anonymous artist; Photograph: Author.)

Figure 6. Drawing of Geronimo on prison wall, Navajo County Museum. (Anonymous artist; Photograph: Author.)

Figure 8. Drawing of the Virgin of Guadalupe on prisonwall, Navajo County Museum. (Anonymous artist; Photograph: Author.)

AN EVOLUTIONARY FRAMEWORK

It is not so much the artifacts that a museum exhibits but their organization that gives form to the “ideological meanings” that they are likely to communicate to the viewer (Bennett 1995:126). Rather than a random “cabinet of curiosities,” or a clustering of items according to individual donors and their ancestors, the objects at the Navajo County Museum are presented in roughly chronological order. The end result is highly reminiscent of the evolutionary ordering of displays in natural history museums that has been soundly critiqued (Ames 1992; Bennett 1995; Jacknis 1985; Leone and Little 2004). The “natural history” model, which situates native peoples in a liminal place between nature and culture, was the dominant exhibitionary paradigm for ethnographic displays in the late 19th and much of the 20th centuries. As Tony Bennett (1995:185–187) has argued, this is an exhibitionary environment that is simultaneously a performative one as the visitor travels through an “irreversible succession” of evolutionary stages. The Holbrook visitor makes such a journey, traveling from primitive inland seas and their early plant and animal creatures, past ancient native artifacts, through stages of early “human” history involving livestock thievery and lawlessness, and culminating in what could be viewed as the apex of civilization, the court of law with its display of an early American flag.

In what ways is the evolutionary framework moti- vated by the logic of settler colonialism? It could be argued that the museum is ethnically inclusive in that it acknowledges the town’s indigenous and Hispanic past in its very first displays. It is in the segregation of these populations as if from the distant past, and from the exhibit’s main narrative, that concerns us here. This segregation is reinforced by the official museum brochure, which summarizes the local past as follows:

This museum tells a brief history of Holbrook and the surrounding area. People from Mexico and Mormon Pioneers settled the Little Colorado River Valley. With plenty of water, lush grasslands, centrally located between the Hopi and vast Navajo Indian Reservations to the north, Fort Apache to the south, and the beautiful Petrified Forest to the east, it soon became the center of commerce when the railroad arrived in 1881. Shown in display cases are pottery, baskets, and rugs used by the three Indian tribes, and items used by early Mexican settlers.17

This text implies that the “people from Mexico” and “Mormon Pioneers” arrived at an uninhabited area located between already-existing reservations. In fact, reservations were established after (and in response to) the arrival of these newcomers or had boundaries that were in flux until quite recently (Walker and Bufkin 1979:44). The fact that lands were expropriated from indigenous users is not mentioned. As Wolfe (1999:179) has argued for Australia, space here is not shared; the “Aborigine” is somewhere else, in this case, segregated onto reservations. Of course, the ample artifacts found by non-Indian residents that we see on display should be testament enough that people have been living in the region for hundreds of years. Holbrook is situated along the Little Colorado River, a tributary to the Colorado River, an important source of water on the arid Colorado Plateau, with evidence of all kinds indicating the region’s use as important grazing, hunting, and farming lands for indigenous peoples.18 Not only were Indians in the area when the “Mexicans” and “Mormon Pioneers” arrived, but many stayed after reservations were created; moreover, intergroup trade and conflict did not end with native confinement onto reservations but has been an ongoing process integrally connected to the emergence and maintenance of local ethnic group boundaries, as we see elsewhere (Kelley and Francis 2001).

By describing Holbrook’s early Hispanic community as “people from Mexico” and “Mexicans,” the text also conflates two populations, more recent immigrants from the later Mexican state and “Hispanos,” Hispanic-origin American citizens from New Mexico who began moving into the area in the 1860s and who were, in fact, the area’s first non-Indian residents. This nuance is completely missing from the brochure.

MAKING HOLBROOK ANGLO

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the portion of New Spain that ultimately became Arizona had minimal Hispanic presence, which was confined to the southern parts of the contemporary state until the 19th century.19 However, “Hispanos” began migrating westward from the “Hispano Homeland” in then New Mexico Territory by the 1860s, and some one thousand two hundred were living in parts of Apache and Navajo counties in Arizona by the turn of the century (Nostrand 1992:91). Their settlements predated those of the Mormon settlers, who founded towns along the Little Colorado River Basin starting in 1876 (Abruzzi 1993; Peterson 1973). We know this because these early Mormon chroniclers mention interacting and trading with Hispanic people already established in the area or moving into their former dwellings (Sorenson and Pulsipher 1999:35). In fact, although Holbrook is framed at the entrance to the museum as established by a Latter-Day Saint (LDS) ancestor, John Young, this account sidesteps the Hispano–LDS rivalry that led to Holbrook’s very location at the outset.

The transcontinental Atlantic and Pacific Railroad was due to arrive in the area in the late 1870s, leading to much competition between local entrepreneurs vying for lands that might prove profitable. Since the railroad would need a depot site somewhere near a good crossing of the Little Colorado River (known for its treacherous quicksands after summer monsoon rains), Young opened a store two to four miles east of present-day Holbrook and sold it to Jesse Smith and other LDS colleagues for their Arizona Cooperative Mercantile Institute, an LDS-run cooperative store (Peterson 1973:1Montaño). He hoped that the railroad company would establish its depot there as well. However, a safe river crossing had already been located at Horsehead Crossing, where Hispano Juan Padilla had lived since 1862 and built a trading post, restaurant, and hotel.20 When the railroad chose Padilla’s location for its depot rather than Young’s site, the LDS leaders tried to obtain land nearby but soon learned that all available land was already in the hands of railroad executive F. W. Smith and wealthy Hispanos Pedro Montaño and Santiago Baca (Smith 1970:228–229).

Pedro Montaño was a prominent sheep raiser from the Albuquerque, New Mexico, area. An 1884 article about the Holbrook region lavished praise on him, stating, “Among the prominent citizens of the community should be mentioned Don Pedro Montano [sic], who owns a large interest in the town company, and is the local agent at Holbrook. This gentleman is known throughout the Southwest for his intelligence, public spirit and enterprise, and he is watching with a sort of paternal interest the growth of his favorite town.”21 His genealogy probably stemmed from an early New Mexican family of the 1754 Montaño land grant outside Albuquerque; his is one of 39 distinctively New Mexican Hispano surnames (Nostrand 1992:8, 91; Simmons 1982:72–85). According to his wife, Alfedis, he “conceived of the idea of laying out the town of Holbrook” with rail- road man Mr. F. W. Smith. He settled the area on November 8, 1881; filed the 160-acre claim on April 14, 1882; received his patent on October 21, 1882; and he and his wife began selling town lots in Decem- ber of 1882.22

Along with Montaño, many of Holbrook’s other prominent capitalists raised sheep, and their business flourished with the completion of the railroad. Holbrook subsequently became the central shipping point for all of northeast Arizona, with livestock and livestock products the most important freight. The non-Indian–owned sheep population in Arizona leapt from 803 in 1870 to over 76,000 in 1880 and almost 700,000 by 1890 (the Navajo herd was estimated at 400,000 sheep and 100,000 goats at the same time) (Abruzzi 1995:75–98). Sheep were shipped almost equally to the East and West Coasts, while wool was shipped to Albuquerque and East Coast destinations. The amount of wool shipped East from Arizona reached an astounding five million pounds in 1891 (Haskett 1936:30–31). Local sheep raisers faced serious competition with cattle, however, when the Aztec Land and Cattle Company, a consortium of Eastern business and Texas ranching interests, purchased over one million acres of local railroad lands in 1884 and imported some 33 thousand to 40 thousand head of cattle into the area by the end of 1887, along with 100 cowboys (Abruzzi 1995:81). The cowboys, known by their brand as the “Hashknife” outfit, were notorious for occupying water holes and dealing harshly with trespassers. We do not know if competition with cattle herding was the cause, but Montaño eventually moved to St. Johns, home of his wife’s family, where he purchased a ranch from renowned trader Lorenzo Hubbell.23

WHAT'S IN A NAME

Names and naming events figure in this small museum in several important ways. First, we might ask which individuals depicted in the collections are even identified by name. Not surprisingly, the vast majority are Anglo-Americans, including Henry Holbrook, John Young, Sheriff Owens, and the other lawmen displayed in the display case outside the Sheriff’s office. Even a young Anglo girl is named in a newspaper article displayed near the collection of dinosaur and indigenous artifacts. Aside from Manu- elito, whose painting appears in the first room, people of other ethnicities are largely nameless: we see unnamed Navajo youth cardboard cutouts, nameless Navajos in romantic paintings of hogans, and an Indian woman from distant Yuma, Arizona, of unknown tribal affiliation in a curious photograph with a bird on her head. The unspoken message is that the important actors in this local history are represen- tatives of the dominant settler society.

Naming places can be politically charged acts of authority and control (Azaryahu 1996:311; Azaryahu and Golan 2001:181; SolÓrzano 1998). The two naming episodes highlighted in the collection, the naming of Show Low, Arizona, and Holbrook, were the work of Anglo men. The story of Holbrook’s naming is one of the first texts the visitor encounters. Paul Carter (1987:152) has argued that settler history first requires the creation of place out of space, the delineation of a “potentially nameable zone.” We could interpret the Holbrook naming event in this vein, as an event establishing “Holbrook the place” before proceeding to its history. This naming event does more, however, for it also silences the town’s Hispanic origins. By explaining that it was John Young, son of LDS leader Brigham Young, no less, who gave Holbrook its name, the text implies that Young was Holbrook’s founder, and associates Holbrook with the string of nearby LDS towns developed along the Little Colorado River in the 1870s (Abruzzi 1995; Peterson 1973). The town’s actual establishment by a coalition of railroad executives and Hispanic elites is completely ignored.

Naming events are often acts of re-naming that follow regime change (Azaryahu and Golan 2001). This is the case in Arizona, as in much of the Southwest, where Native American and Hispanic-language place names were rarely honored by white Anglo settlers, in contrast to Spanish colonial practice (Jane Hill 1993, 2008:85; SolÓrzano 1998:109). The nearby town of San Juan is now St. Johns. What was the “Rio Colorado Chiquito” in 1884 is now the Little Colorado River.24 And even Pedro Montaño’s role in Holbrook’s history was minimized in 1941 when a “consultative committee” carried out a systematic renaming of the city streets: Montaño Street, which ran through the center of town, became First Avenue, Alvarado became Second Avenue, and Coronado became Third Avenue. The town’s Anglo name, and the museum’s highlighting of this naming event that associates the town’s origins with Young rather than Montaño, must be seen within the wider settler-colonial context as strategies that valorize and foreground some people and their actions while minimizing others.

BRAVE SHERIFF OR INDIAN KILLER

A noteworthy contrast to silenced town founder Montaño is Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens, who is depicted three times in the displays: his is the central image in a display of local political figures (Figure 9); he is depicted with other former police officers and county sheriffs alongside badges and other materials in a case just outside the jail; finally, he is the hero of the “Blevins’ house shootout,” which we learn about at the beginning of the museum. Museum brochures and flyers praise him as a “fighting man.”25

In fact, Owens had taken the law into his own hands before. Neil Carmony writes that Owens had the reputation of “being tough and fearless,” adding, “in 1883 Owens shot and killed a young Navajo man he thought was stealing livestock” (1997:3). Carmony suggests that actions such as these may have pro- moted him to sheriff: “when gangs of rustlers and hold-up men threatened to take charge of Apache County, the law-abiding citizens turned to Owens for help. The thirty-four-year-old bachelor was elected sheriff in November” (1997:3). This image of Owens- the-frontier-hero appears in another historical soci- ety–authored pamphlet I collected at the museum in 2002:

Into this lawless environment came Commodore Perry Owens, a young man with flowing blond hair and the reputation of being a dead shot. He was hired originally as foreman by the John Walker Ranch at Navajo Springs in 1881, and also held the job of range foreman for the Gus Zeiger outfit, as well as that of guard of the cavalry horses held at Navajo Springs where they were in danger of being stolen. It is said that he killed so many Navajo Indians that he earned the name of “Iron Man”—the Indians deciding that he lived a charmed life and could not be killed. He was as good a shot with his left hand as with his right, wore twin forty-fives at his hips, and carried two rifles in his saddle scabbards.26

Owens appears in Navajo oral history as well, although not as conveyor of civilization and order but as a violent criminal and horse thief (Kelley and Francis 2001:79, 97). According to Navajo oral sources, he homesteaded near Navajo Springs in the late 1870s. This was a period of flux when Navajos on lands south of the reservation that had become part of the railroad grant in 1866 collided with “incoming self-styled Americans,” non-Indian cattle ranchers who hoped to profit from sales in distant markets made accessible by the new railroad and from government contracts (Kelley and Francis 2001:74). Much of the violence during the 1870s and 1880s in this area stemmed from conflict over water rights. Indian Agent Riordan described him in scathing prose in 1883 after he allegedly shot the son of a Navajo chief:

These men Owen and Houck are men dangerous to the peace and good order of this region. I saw over twenty-five Indians who have been shot at by them during the past year or two, including an Indian woman. I despair of securing a conviction of either of them; and realize that I am liable to be assassinated by them for having undertaken to punish them for their crimes. [Kelley and Francis 2001:82]

That neither Navajo nor Indian agent perspectives on Owens appear anywhere in this exhibit further underscores its settler-colonial orientation. Wolfe’s work is again illuminating. In his discussion of frontier violence, he writes that the activities of the frontier rabble constitute its principal means of expansion, adding, “once the dust has settled, the irregular acts that took place have been regularized and the boundaries of White settlement extended. Characteristically, officials express regret at the lawlessness of this process while resigning themselves to its inevitability” (Wolfe 2008:108). In 19th-century Arizona territory, by electing this “Indian killer” to be their sheriff, voters were condoning his “irregular” past behavior, and even today’s museum lauds his killing of three suspects. In a marked contrast to living history museums, which often present an artificially harmonious depiction of local social relations (Bennett 1995:114), in the settler-colonial consciousness, conflict is foregrounded, even celebrated.

Figure 9. Law and order. Detail of exhibit, Navajo County Museum. Owens is on the left. (Photograph: Author.)

BEYOND HOLBROOK: NEARBY COUNTIES, COMMON ORIGINS

This museum is not unique; in fact, I would argue that strikingly similar depictions of the local past could be found in collections across the region, if not the country. Consider, for instance, other Arizona museums such as the Apache County Historical Society Museum in St. Johns, the Graham County Historical Museum in Thatcher, and the Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society of Graham County in Pima (see Figure 1). These museums are all located in small towns in counties with similar demographics: they are among the poorest of Arizona’s counties, are sparsely populated, have high unemployment rates, and include or are adjacent to Indian reservations. Each of these museums was the work of local residents of primarily Anglo and LDS origins with long-standing ties to the area. The historical societies in charge of them are dominated by people of the same backgrounds. Strong connections to local political structures were necessary to secure initial funding and are needed for continued support. They are staffed largely by volunteers. Collections were secured locally, principally by donations, and include many items of the founders’ ancestors, such as quilts, old tools, and vehicles. Not surprisingly, the past celebrated in these collections is strikingly similar to that of the Navajo County Museum.

The Apache County Historical Museum in St. Johns is a case in point. Sponsored by the St. Johns Rotary Club in 1973, it is widely known as the under- taking of Mr. and Mrs. Dewey Farr, descendants of an early LDS family.27 Dewey Farr explained his connec- tion to this project:

From the lips of my father and mother, and many other early settlers of the late 1870s or early 1880s, I have listened to experiences and historical incidents which deeply impressed me. Their courage and determination to succeed, in the face of diversities and trials [sic], made history which needed to be preserved. So after being given the position of “President,” Mrs. Farr and I have spent most of our time, and all our “whiskey” money in organizing, collecting funds, and building this beautiful museum.28

As in the Holbrook example, preserving a defunct historical structure was the impetus for this project—in this case, the structure was an old log cabin that belonged to the Farr family, who also provided the land for the museum complex.29 Since the cabin was too small to hold the collection, a new structure was commissioned and funded by a grant of $126,000 from the Environmental Development Agency and $32,000 from local families.30

The spatial organization of the collection is similar to that of Holbrook, with an initial focus on the town of St. Johns with a series of historical photos of the town in yesteryear and a scale model of the town center (rather than a focus on the county as a whole), followed by a roughly chronological display of what I label “Prehistory,” “Hispano” history, and “Pioneer” history. On two occasions, display cases exhibit prehistoric fossils immediately adjacent to indigenous artifacts. While the Hispanic presence in the area is granted more attention here than in Holbrook (represented by an exhibit on the “First families of San Juan”), imagery found in a central diorama undermines this effort. This diorama features four displays of ethnic group histories that include Indian figurines hiding behind rocks before arriving Spanish conquistadors, Mormon settlers standing upright with hoes working the land, Navajo lounging on the ground near their hogans while sheep graze nearby, and “Hispano” shepherds represented by a sleeping figurine wearing a giant sombrero.

The preeminence of settler artifacts in this collection again reveals the settler as principal protagonist of local history. Even more than the Holbrook museum, the Apache County Historical Museum could be viewed as part elaborate family shrine. Several display cases feature the artifacts, portraits, and family history narratives of the town’s prominent LDS and Anglo families, organized by family, with ancestors’ former possessions such as quilts, canes, and a pewter serving set displayed alongside their portraits and genealogical information. An employee of the St. Johns Chamber of Commerce, which helps staff the historical museum, explained that the Farrs “looked far and wide for items,” and added that they “needed to be the long-term, well-established family that they were to get so much material, as they had to twist the arms of a lot of folks to get them to donate.”

As in Holbrook, Anglo individuals dominate the collection in other ways: settler artifacts are usually identified by ancestor or descendant, while Indian artifacts are often of unknown provenance. Sometimes artifacts of the same type, such as pottery shards, have been organized in some symmetrical pattern and framed. If they were associated with any one individual by name, it would be the Anglo person who found them, framed them, and donated them to the collec- tion.Wefind a similar situation in the Eastern Arizona Museum in Pima that has an “Indian Room” filled with a “large sampling of southwestern artifacts, such as pots, bowls, axes, knives, grinding stones, paint pal- lets and such, with most coming from the local area.”31

Each of these collections had idiosyncratic beginnings, usually rooted in a serendipitous conjuncture of energetic local personalities, available space, resources, and objects. The Graham County Historical Museum has been based at a vacated local school but will have to move shortly when the school board reclaims this space.32 The Eastern Arizona Museum is located in an abandoned bank that had been in the founders’ family, in the tiny town of Pima, Arizona. One of its founders told me the collection started almost by accident:

What started it was this, we had this guy, and he retired, had a stroke. He wasn’t a real people person, but he had a Jeep, and he would travel all around and collect a lot of Indian artifacts. He needed a place to store it—his wife finally said she didn’t want it in the house. My husband was into archaeology, so that’s how they got started. At first, our record keeping wasn’t the best. People would bring things in, and I’d write it down.33

The fact that these museums were established by descendants of the local Anglo elite helps explain the rather unselfconscious settler orientation of the exhibits and the concomitant downplaying of other local histories. However, the label “county” museum, and the fact that these museums secure funding from county coffers and state-wide historical societies, gives the uninformed visitor the impression that these exhibits are county-sanctioned, or at least aim to document county-wide pasts.

EVOLUTION AND THE SETTLER-COLONIAL PAST

Deborah Bird Rose asks how it is that we “new world” settler peoples come to imagine that we belong to our beloved homelands: “We cannot help but know that we are here through dispossession and death. What are some of the stories we tell to help us inscribe a moral presence in places we have come to through violence?” (2006:228). I have tried to show some of these stories here. In these historical museums, Indians are presented as if they were from the remote past, or even part of the natural world, with their material objects located next to dinosaur remains. The message is that while they may have lived right here, they are now gone. By the time “we” arrived, “they” were living on reservations carrying out traditional occupations. The towns owe their existence to the early Anglo “pioneers” who brought commerce and civilization, and whose descendants continue to hold positions of power. Yet, this is clearly not the whole story. In Holbrook, it neglects so much, including a fascinating Hispano–Anglo rivalry and a continued indigenous presence that has been reduced to prison drawings.

Couldn’t one argue that this is the only way to organize the local past in this part of the country? It is time to revisit the evolutionary exhibitionary paradigm in light of our discussion of settler colonialism. As noted, one of its distinctive features is its positing that all of humanity evolves along a similar track, with “primitive” contemporaries representing people stuck in earlier stages. Historian Steven Conn (2006:94) has described this as a distinction in chronometers, with Native Americans existing in a “natural time” like animal species or geological formations. Scholars have criticized the paradigm’s racism, its Eurocentrism, and the fact that Native Americans are not treated as equals. Mark Leone and Barbara Little for instance, write that most “modern Americans don’t see natural history museums as pessimistic or imprisoning, but Native Americans do as in them they see themselves ranked below modern Western human beings” (2004:372). Yes, the relegation of Indians to the past is problematic on so many levels, and a subhuman ranking has multiple, lasting effects. What Leone and Little and other critics neglect to explore (but which their work surely anticipates) is the ways the evolutionary trope is especially necessary for narrating the past in an ongoing settler colonial society.

Not only does the evolutionary model relegate peoples to different human races or types, or to different chronometers altogether, conjuring up notions of indigenous extinction, but it also allows us to imagine the progression of populations as an orderly succession rather than emphasizing the violence of their actual collision. As part of settler colonialism’s “logic of elimination,” it works to screen from view the messy era of conquest that culminated in the dispossession of the area’s original inhabitants, a saga that would certainly make some visitors uncomfortable. The “other” people are removed so that their artifacts become simply the stuff that “we” found when “we” arrived. Thus, the narrators of what Leone and Little refer to as an “Anglo-American way of categorizing the world” are not only Anglos but also, more specifically, settlers, and it is assumed that the museum audience will be too (Leone and Little 2004:394). In the American Southwest, the Hispanic settlement history is particularly problematic, for it threatens to call into question the entire narrative thrust, and at least in this part of Arizona, it is kept at the margins.

Wolfe (1999) observes that Aboriginal and European societies in Australia are depicted as occupying discontinuous spheres, either different eras altogether or wholly different places. The images of Aboriginality that figure most prominently are those that “least conflict with settler-colonial economics” (Wolfe 1999:180). We find a strikingly similar pattern in many Arizona museums, with romantic paintings of “traditional” Indians found alongside stories of heroic Indian killers, such as Sheriff Owens, who helped eliminate whatever economic competition existed when Anglos were first arriving to the scene. The relegation of the Indian off-stage or to a precivilization lifeway is necessary to grant these towns moral legitimacy. Moreover, local people that would blur social categories and thus call into question the implied evolutionary model, such as “Indian cowboys,” contemporary Apache or Navajo citizens, or the town’s early Hispanic entrepreneur-founders, such as Montaño, remain off-stage.

The ubiquity of the evolutionary exhibitionary model in the United States has been shaped by not only the nation’s settler colonial heritage but also a generalized denial of this heritage today. Such a perspective is not limited to smaller, poorly funded public history operations, but persists, even in profes- sional historiography (Adas 2001; Colwell-Chantha- phonh 2007:3–4; Kaplan 1993:17; Tyrell 2009:544).

WHAT IS A MUSEUM TO DO?

Were curators in these rural, economically depressed counties purposefully trying to construct a “settler- colonial”museum or trying to alienate non-Anglo visitors? Certainly not. By all accounts, Garnett Franklin, the force behind the Holbrook museum, sacrificed years of her life to communicate her love of the past to outside and local visitors through not only the museum but also in regular newspaper columns on local history and by speaking to school classes in the area. In many ways, she has fulfilled Schlereth’s agenda for the history museum: she has spent much of her life’s energy trying to show “the average citizen” ways of “knowing themselves and their communities through an understanding of their own past” (2004:344). But, we must ask, “which citizen” and “which past”?

Museum founders certainly had family members in mind: the exhibits that include ancestors’ treasured possessions and portraits, held on loan and accompanied by lengthy genealogies, are understandably geared toward their surviving relatives living locally or visiting periodically from afar. In this regard, the museums play a role parallel to those Native American museums found on the nearby reservations that have adopted a predominant in-group focus and pedagogical mission (Hoerig 2010:70).

More difficult to address is the fact that the imagined audience includes tourists. Tourist dollars are especially important motivators when small towns anywhere face economic decline. As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett reminds us, “Heritage adds value to existing assets that have either ceased to be viable (subsistence lifestyles, obsolete technologies, abandoned mines, the evidence of past disasters) or that never were economically productive because an area is too hot, too cold, too wet, or too remote or that operate outside the realm of profit” (1998:150).

While I would never argue that the local historical society held merely a utilitarian regard for the local past, it is clear that Franklin also hoped to see her town prosper and was aware of the powerful draw of the “mythic Old West” in the American imagination. In an article about the museum that appeared in 1990, Franklin states, “travelers from the East are usually awed by Holbrook’s history. Visitors can view the sheriff’s office and almost feel the warmth from the old pot-bellied stove or hear the jingle of spurs as the deputies come in from looking for rustlers on a cross country ride” (Fox 1990). She continues, “we see the appreciative looks of the public, who often feel as though they have just rediscovered the West, and feel firsthand the life the early settlers of the area lived,” adding as almost an afterthought, “local citizens are encouraged to visit the museum too” (Fox 1990).

These passages suggest a specific audience for the exhibits—faceless “Easterners” seeking the mythic West (Nash 1991). One imagines that these museum founders developed collections in part in reaction to the perceived demands of tourists, who, like the founders, held particular expectations for the “Old West” shaped by TV westerns, historical novels, and 19th- century understandings of the frontier (DeLyser 1999:610). What is crucial here is the presumption that this audience will share a settler orientation on this past as well. This is perhaps more apparent when we consider these museums’ location in counties that also host large Indian reservations. In fact, at the Holbrook museum, the native peoples a visitor is most likely to encounter are those hired to dance in the museum grounds for tourists during the summer months.

Given these problems and dilemmas, what direction should our local museums take? In his discussion of historical consciousness, Peter Seixas writes of the need to consider “value commitments”: in part to contribute to “public-policy applications,” scholars of historical consciousness “must accept the burden of normative judgments: different forms of historical consciousness are supported by and, in turn, promote different social and political arrangements” (2004:10–11). Referencing “high levels of migration,” he writes that some “forms of historical consciousness that may have been acceptable for relatively homogenous cultures pose obstacles to the negotiation of inter-group relations and adaptation to rapid change that characterize postmodern global culture” (Seixas 2004:11). The problem here, however, is not one of adding another layer of multivocality due to new waves of immigrants or a diversifying society; it is not simply a matter of opening up the museum to other forms of historical consciousness, but it is more intractable. The fact that systematic steps were not taken to involve represented communities in the initial exhibition planning reveals much about the settler colonial legacy of this country, which has included mild to extreme racial prejudice as well as structural racism, especially in border communities, unequal power sharing within the towns in question, and a general marginalization of local native and Hispanic community members. A temporary solution would be to rename these museums to more accurately reflect their settler focus. The more difficult challenge is to find some way to step outside the settler orientation altogether and present a story that people—of all backgrounds—will want to come to see. For, when one people’s triumph is another people’s tragedy, what kind of shared narrative is possible, and how might it be expressed?

In conclusion, the dedicated museum founders and directors may have recognized the potential of these collections in bringing added value and, hopefully, income to the coffers of their economically depressed towns. However, by appealing to their imagined (non-Indian, non-Hispanic) visitor, they ended up communicating hegemonic understandings of the national past and local society. In an effort to present a local historical narrative to the “average [settler] citizen,” they helped foster and perpetuate a settler-colonial historical consciousness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Versions of this paper were presented at the conference Language, Ideology and Semiotics, May 2009, at the Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, and the panel The Ends of Settler Studies: Settler Colonialism and Nostalgic Anthropology at the 2009 Annual Meet- ing of the American Anthropological Association. Many thanks to conference and panel organizers Heidi Orcutt- Gachiri and Tamara Neuman. The present version was strengthened by comments from William Abruzzi, Alli- son Alexy, Anna Eisenstein, and anonymous reviewers as well as the editors and editorial manager of Museum Anthropology. Research was conducted while I was scho- lar at the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, Iowa. I thank Jay Semel and the center staff for support throughout my stay there and Lafayette College for the research leave that made this work possible. Research assistance was graciously provided by Liang Zhang and Brooke Kohler.

NOTES

- This study is based on more than a dozen site visits over an eight-year period, interviews with docents, museum curators, members of the Navajo County Historical Society, local family history center staff, journalists, city officials, and residents. Many thanks to the members of the Navajo County Historical Society, especially Mary Barker and Zelda Gray for their efforts in tracking down sources, and to JoLynn Fox for her enthusiastic assistance. Early site visits were enhanced by the astute comments of Lafayette student Jenny Roberts.

- www.aam-us.org/aboutmuseums/abc.cfm, consulted April 8, 2011.

- http://iweb.aam-us.org/Membership/MemberDirectory- Search.aspx, consulted February 1, 2011.

- Annual budgets (of less than $100,000), number of staff members, and square feet of exhibition space were the most prominent criteria cited by the survey’s 455 respondents. See www.aaslh.org/SmallMuseums.htm, consulted February 1, 2011.

- “County’s Historical Society Discusses Courthouse’s Future,” Holbrook Tribune-News, February 16, 1976, 8.

- “Holbrook City Council Urged to Preserve Old Courthouse,” undated newspaper article, Navajo County Historical Society clippings folder, Holbrook, AZ.

- J. F. interview, interview, 2009.

- “Nine Citizens Appointed to County Museum Board,” Holbrook Tribune-News, undated article, clippings folder, Navajo County Historical Society, Holbrook, AZ.

- “Welcome to the Historic Navajo County Courthouse,” flyer collected in 2002, hereafter, “Guide.”

- “Work Continues on County Museum,” undated article, clippings folder, Navajo County Historical Society, Hol- brook, AZ; “Over 1,400 Visit County Museum,” Holbrook Tribune-News,” September 21, 1983, 1.

- The subheadings here are my own, developed for heuristic purposes.

- Guide 2002:1.

- “Holbrook. A Legend of the Old West,” one-page typescript collected in 2002.

- “Manuelito, the once fierce chief of the Navajo,” published between 1887 and 1901, Denver Public Library.

- Guide 2002:2.

- Guide 2002:3.

- Guide 2002:1.

- The river is an important site in Zuni and Hopi migration narratives, and today’s town is near the ancient Zuni- Hopi Trail (Durrenberger 1972:211–236; Ferguson and Hopi Trail (Durrenberger 1972:211–236; Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2006:152–155, 106; Spicer 1962: 229–230). On Navajo uses of the area, see also W. W. Hill (1938).

- Spanish explorers had arrived in the 16th century when Coronado passed through the area on his way to Zuni in 1540, and Franciscan missionaries maintained a presence among the nearby Hopi Indians from 1629 until evicted in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt (Officer 1987:3–5).

- “Horsehead Crossing: Location Still under Study by Local Residents,” Holbrook Tribune, July 2, 1981.

- Ecce Montezuma, April–August 1884, Item 5, Periodical Box 37, Sharlot Hall Museum, Prescott, AZ, 47.

- Apache County Grantor Book 1, pp. 169, 183, books 2, pp. 34, 40; Grantee Book, Deeds 2, pp. 1–250. See Soza, “Hispanic Homesteaders in Arizona 1870–1908 under the Homestead Act of May 20, 1862 and Other Public Lands,” typescript, 1994, Northern Arizona University Special Collections, Flagstaff, AZ.

- “Alfedis Montan˜o, True Pioneer,” typescript, n.d., Item 5, Folder 1, Article Box 2, Sharlot Hall Museum, Prescott, AZ.

- Ecce Montezuma, 45.

- Typescript flyer, collected 2005.

- “Highlights of Early Holbrook,” typescript, March 1973, emphasis added.

- Apache County Independent News, August 24, 1973. Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Ephemera collection.

- “Footprints of Time,” p. 32, n.d., Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Ephemera collection.

- “Footprints of Time,” p. 33.

- Phoenix Gazette, August 27, 1973.

- Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society of Graham County brochure, collected April 2004.

- Graham County Historical Society Newsletter, December 2010. One can now tour the collections “virtually”: www. grahammuseum.org, consulted March 24, 2011.

- Conversation with C. W., March 1, 2004.

REFERENCES CITED

Abruzzi, William S.- 1993 Dam That River! Ecology and Mormon Settlement in the Little Colorado River Basin. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- 1995 The Social and Ecological Consequences of Early Cattle Ranching in the Little Colorado River Basin. Human Ecology 23(1):75–98.

- 2001 From Settler Colony to Global Hegemon: Integrating the Exceptionalist Narrative of the American Experience into World History. American Historical Review 106(5):1692–1720.

- 1992 Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- 1996 The Power of Commemorative Street Names: Environment and Planning D. Society and Space 14:311–330.

- 2001 (Re)Naming the Landscape: The Formation of the Hebrew Map of Israel 1949–1960. Journal of Historical Geography 27(2):178–195.

- 1995 The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. New York: Routledge.

- 2005 Imagined Geographies: Sovereignty, Indigenous Space, and American Indian Struggle. American Ethnologist 32(2):239–259.

- 1997 Editors Introduction. In Gunfight in Apache County, 1887. The Shootout Between Sheriff C. P. Owens and the Blevins Brothers in Holbrook, Arizona as Described by Will C. Barnes. Pp. 1–7. Tucson, AZ: Trail to Yesterday Books.

- 1987 The Road to Botany Bay: An Exploration of Landscape and History. New York: Knopf.

- 2007 Massacre at Camp Grant: Forgetting and Remembering Apache History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- 2006 Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 2010 New Directions in the Sociology of Collective Memory and Commemoration. Sociology Compass 4(7):442–453.

- 2006 Rethinking Settler Colonialism: History and Memory in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and South Africa. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- 1999 Authenticity on the Ground: Engaging the Past in a California Ghost Town. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89(4):602–632.

- 1972 The Colorado Plateau. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 62(2):211–236.

- 2006 History Is in the Land: Multivocal Tribal Traditions in Arizona’s San Pedro Valley. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- 1990 Holbrook’s Museum Offers Window to the West. Holbrook Tribune-News, March 16.

- 2010 Asian Settler Colonialism: From Local Governance to the Habits of Everyday Life in Hawai’i. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- 2006 Persons of Stature and the Passing Parade: Egalitarian Dilemmas at Monticello and Colonial Williamsburg. Museum Anthropology 29(1): 5–19.

- 1997 The New History in an Old Museum: Creating the Past at Colonial Williamsburg. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- 1936 History of the Sheep Industry in Arizona. Arizona Historical Review 7:3–49.

- 1938 The Agricultural and Hunting Methods of the Navajo Indians. Yale University Publications in Anthropology No. 18. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- 1993 Hasta La Vista Baby: Anglo Spanish in the American Southwest. Critique of Anthropology 13(2):145–176.

- 2008 The Everyday Language of White Racism. West Suffex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- 2010 From Third Person to First: A Call for Reciprocity Among Non-Native and Native Museums. Museum Anthropology 33(1):62–74.

- 1985 Franz Boas and Exhibits: On the Limitations of the Museum Method of Anthropology. In Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture. George Stocking Jr., ed. Pp. 75–111. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- 2009 WhiteMother to aDarkRace: SettlerColonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- 1995 Heterotopic Dissonance in the Museum Representation of Pacific Island Cultures. American Anthropologist 97(2):324–338.

- 1993 “Left Alone With America”: The Absence of Empire in the Study of American Culture in Cultures of U.S. Imperialism. In Cultures of U.S. Imperialism. Amy Kaplan and Donald Pease, eds. Pp. 3–21. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- 2008 Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- 2001 ManyGenerations,FewImprovements:Americans Challenge Navajos on the Transcontinental Railroad Grant, Arizona, 1881–1887. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 25(3):73–101.

- 1998 Destination Culture. Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 2004 Artifacts as Expressions of Society and Culture. Subversive Genealogy and the Value of History. In Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts. Bettina Messias Carbonell, ed. Pp. 362–374. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- 2007 Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities. Lanham, MD: Alta Mira Press.

- 1999 Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. New York: The New Press.

- 2004 Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History. New York: Bergahn Books.

- 1991 Creating the West: Historical Interpretations 1890–1990. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- 1992 The Hispano Homeland. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1987 Hispanic Arizona, 1536–1856. Tucson: Univer- sity of Arizona Press.

- 1973 Take Up Your Mission: Mormon Colonizing along the Little Colorado River 1870–1900. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- 2005 U.S. Colonial Law and the Creation of Margin- alized Political Entities. American Ethnologist 32(3):406–419.

- 1999 Garnette Franklin Honored at Holbrook Council Meeting. Holbrook Tribune-News, July 16.

- 2006 New World Poetics of Place: Along the Oregon Trail and in the National Museum of Australia. In Rethinking Settler Colonialism: History and Memory in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and South Africa. Annie E. Coombes, ed. Pp. 228–244. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- 1998 The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

- 2004 Collecting Ideas and Artifacts: Common Problems of History Museums and History Texts. In Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts. Bettina Messias Carbonell, ed. Pp. 335–346. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- 2004 Introduction. In Theorizing Historical Consciousness. Peter Seixas, ed. Pp. 3–20. Toronto: University Toronto Press.

- 1982 Albuquerque: A Narrative History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- 1970 Six Decades in the Early West: The Journal of Jesse Nathaniel Smith. 3rd edition. Provo, UT: Jesse N. Smith Family Association.

- 1998 Struggle Over Memory: The Roots of the Mexican Americans in Utah, 1776 through the 1850s. Aztlán 23(2):81–117.

- 1999 History of David Pulsipher 1828–1900: His Ancestors and Descendants. Bountiful, UT: Family History.

- 1962 Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest, 1533–1960. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- 2009 Empire in American History. In Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State. Alfred McCoy and Francisco Scarano, eds. Pp. 541–556. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- 1979 Historical Atlas of Arizona. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1996 Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- 1999 Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London: Cassell.

- 2008 Structure and Event. Settler Colonialism, Time, and the Question of Genocide. In Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. A. Dirk Moses, ed. Pp. 102–132. New York: Berghahn.